Right now, the attention of most Americans is, understandably, captured by the latest developments of the COVID-19 pandemic and the national debate over criminal justice. But the 2020 presidential election continues to trod along in the background, and Wall Street is starting to worry about the outcome.

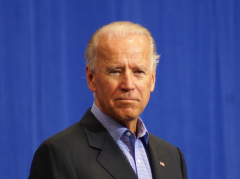

The New York Times reports that investors are growing alarmed over Joe Biden’s rise in the polls. Some worry that his promised massive tax hikes and sweeping regulations could spell doom for the stock market and hurt business more broadly. However, it’s not just stockbrokers on Wall Street and 401k holders relying on the market for retirement who should be worried.

Joe Biden’s regulatory platform would eliminate entire industries and therefore millions of jobs—including my own. Supposedly, the appeal of Biden’s presidential campaign is a return to stability. Yet his platform includes endorsements of radical regulations that would undermine the economy as we know it.

Consider Biden’s stated support for California’s AB 5, a crushing regulation that has killed too many jobs to count in the Golden State. The former vice president has endorsed similar regulation on the federal level.

The California bill was supposedly introduced to help the state’s roughly one million independent contractors by severely limiting the amount of work freelancers can do in an attempt to compel employers to add them onto payroll as full-time employees. The rule was supposed to stop “exploitation.” In reality, it stripped flexibility from thousands of Californians who didn’t want to be full-time employees while prompting companies to let contractors go, not hire them on.

From artists to musicians to freelance journalists to Uber drivers, thousands of California workers saw their livelihoods snuffed out by this bill. Even the original sponsor of the law, state Assemblywoman Lorena Gonzalez, admitted she was “wrong” in response to angry freelancers who lost work.

Under social media trends like #AB5Stories and in direct replies to Biden, countless Twitter users have spoken out—many of them left-leaning California residents—against the candidate’s position:

In the absence of any response from the presumptive Democratic nominee, we can only assume that Biden still supports this proposal, which would erase millions of American jobs, from Uber drivers to journalists, with the stroke of a pen.

This would affect me personally—making my current income and livelihood illegal.

After completing a one-year journalism fellowship in June, I entered the job market at perhaps the worst possible time due to the peak of COVID-19 and a looming recession. Frankly, I struggled to find full-time work. But I was soon able to cobble together a full-time income through regular freelance writing gigs with several outlets. Now, I get to wake up every morning and do the kind of writing I love, with near-complete flexibility in my schedule and a solid income.

Yet I could not do this under AB 5, which arbitrarily limits freelancers to 35 articles for any given publication per year. This bill would make even writing a weekly column for one publication as a freelancer illegal. A full-time freelance journalism career under this regulatory regime would, in most cases, be impossible.

These job-killing regulations would take livelihoods away from millions of Americans. But it’s not just us: The former senator also supports a regulatory change that would destroy social media and the technology sector.

Biden has backed repealing Section 230, the provision which gives social media platforms such as Twitter and Facebook liability protections for the content that users post. It has been dubbed the law that “created the internet,” and only by holding users, not companies, liable for their posts can platforms even exist. Just imagine how much potentially defamatory content gets posted to social media every day, and you’ll quickly realize why repealing Section 230 would immediately put Silicon Valley out of business—and put hundreds of thousands of Americans out of a job.

Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, YouTube, and more would all disappear in short order. Or, at the very least, they would radically transform, and be forced to delay user posts until they can undergo a vetting process that, given the number of posts each day, would quickly grow backlogged and overwhelmed. Yet the US technology sector couldn’t exist for long with these kinds of burdens thrust upon it by the long arm of the federal government, and its collapse would likely be inevitable.

Biden’s support for job-killing regulations extends beyond independent contracting and the tech industry to many other walks of American life. The candidate’s wrong-headed agenda reminds us of a stubborn lesson big government advocates rarely seem to learn: Unintended consequences will always plague sweeping mandates put together by politicians and bureaucrats huddled together in the nation’s capital hundreds of miles away from the on-the-ground realities of the jobs they’re regulating.

From accidentally worsening a city’s cobra infestation to car environmental regulations leading to a spike in taxi use and hence more pollution, history abounds with examples of well-intentioned regulators making things worse by overlooking the unintended consequences of their actions.

Here’s how FEE’s Antony Davies and James R. Harrigan summed up this key lesson:

Lawmakers should be keenly aware that every human action has both intended and unintended consequences. Human beings react to every rule, regulation, and order governments impose, and their reactions result in outcomes that can be quite different than the outcomes lawmakers intended. So while there is a place for legislation, that place should be one defined by both great caution and tremendous humility. Sadly, these are character traits not often found in those who become legislators.

The lesson is clear: pure intentions do not necessarily result in positive outcomes.

“It’s not enough… to endorse legislation that has a nice title and promises to do something good,” economist Robert P. Murphy also wrote for FEE. “People need to think through the full consequences of a policy, because often it will lead to a cure worse than the disease.”

And elections are no exception. If the American people let Joe Biden have his way with our economy, there will be unintended consequences—that could cost you your job.

Brad Polumbo

Brad Polumbo is a libertarian-conservative journalist and the Eugene S. Thorpe Writing Fellow at the Foundation for Economic Education.

This article was originally published on FEE.org. Read the original article.